I embarked on my year of academic development with the goal of making operating less painful for surgeons. The field of surgical ergonomics is nascent, and while there is an appetite for technological solutions, behavioral interventions are one of the only effective (albeit limited) tools available to us right now. With this understanding, my first project was to implement intraoperative microbreaks (short, 90 second pauses taken intermittently during an operation to stretch and break up sustained positions without breaking scrub) as a department wide intervention. While microbreaks don't prevent injury, they have been shown in some studies to reduce pain and improve focus. Moreover, I thought that such a low cost, low tech solution would be easy to implement. What I didn’t realize was that not only was culture change itself an ambitious goal, but also that achieving it required a relentless extroversion formidable to my introverted self. I quickly realized that this endeavor would be one of the most challenging things I have ever had to do.

Before implementing microbreaks, I wanted to understand how much pain surgeons were in. We chose a series of ten operations to start with and decided to send surveys to surgeons and residents before and after each instance of one of the selected cases. Even with this, I faltered. How can we ask busy, overworked, and burnt-out surgeons and residents to fill out a survey with seemingly no immediate benefit? I remember as a clinically active resident, I loathed every survey that appeared in my inbox and resented every person who asked me to do just one more thing. I even enrolled in a study in which I got a free smartwatch, but categorically refused to take on the extra work of setting it up and never used it. From the very start of this year’s journey, I felt like a hypocrite.

Keeping this in mind, I tried to make my “pain surveys” as painless as possible. The goal was to get the answer to just two questions: 1. Do you have pain? And if the answer is yes 2. Where and how much? I tried many different modalities and iterations. I printed out cards with body maps and left them in the operating room, but no one filled them out. Then, I tried running between rooms to catch teams as they were finishing and asked them directly. This was effective, but impossible to scale and sustain over the long term. Finally, I developed a survey on Qualtrics that utilizes the “hot spot” function on an image of a body map, and got feedback that residents and faculty enjoyed the clickable, touch-screen interface.

In the first couple of days, I manually created Qualtrics links daily and personally texted them to each surgeon and resident I was studying, constantly eying the OR board to figure out when to send the pre and post-operative surveys. Realizing that this too would not be scalable, I taught myself Python by watching a YouTube tutorial and wrote a program that could automatically create custom Qualtrics links with the surgeon name and operation pre-filled and send them out at specified times using Twilio, an automated text messaging service. There were two problems with this approach. First, the times I programmed in were the scheduled case start and case finish times which did not account for delays or schedule changes. I knew these times could be inaccurate but it was a limitation I had to live with given my current lack of resources, technical expertise, and inability to integrate my program with the Epic EHR. The second problem was that I often didn't know which resident would be scrubbing the case when I ran my program the night before to generate the links. Cases were not always assigned at the beginning of the week and last minute switches were frequent especially on some of the more unpredictable services. As such, surveys would often be sent to the wrong resident. I finally embedded myself in the case assignment emails for some of the services which alleviated this issue to a degree.

To my great surprise, attendings loved the survey and responded most of the time. I'm not sure why they participated enthusiastically - perhaps this survey was filling a void that had been unaddressed for too long. Residents - not unexpectedly - rarely responded. When not operating, residents are seemingly constantly playing catch up with floor updates. Perhaps incentivizing this process for residents, whereby their cases can be logged automatically in the ACGME case log, could improve response rates. This is a direction we could pivot to or explore in our next iteration. In retrospect, the correct thing would have been to observe residents as they received the notifications and understand their behaviors - using this to understand why people weren't responding and appropriately pivoting the approach. Overall, we have collected 1000 data points since rolling out the automated surveys six months ago.

Throughout the process, I confronted my fear “bothering others” constantly. Iteratively improving on the survey design and delivery process required me to interrupt residents at work, watch them go through the survey, and ask them to share their insights and feedback with me. But the end result speaks for itself. Far from a finished product, it is still a massive step forward from doing and measuring nothing.

With the pre-intervention data collection process semi-automated and underway, it was time to design and implement the microbreaks themselves. I looked into existing resources, such as OR-Stretch from the Mayo Clinic, a web-app on which the surgeon programs an alarm at set intervals that prompts and guides the OR team through a microbreak. I shared this freely-available resource with many of our surgeons for feedback and learned that 1) surgeons didn’t want an alarm going off in their OR that would rely on the circulator staff to manage and 2) we had no reliable way to display the web-app's video on screens in the OR. However, surgeons did note that they would be willing to take microbreaks during predetermined natural break points in the case. With this feedback, I went back to the drawing board to design a resource that would better fit the needs of our surgeons.

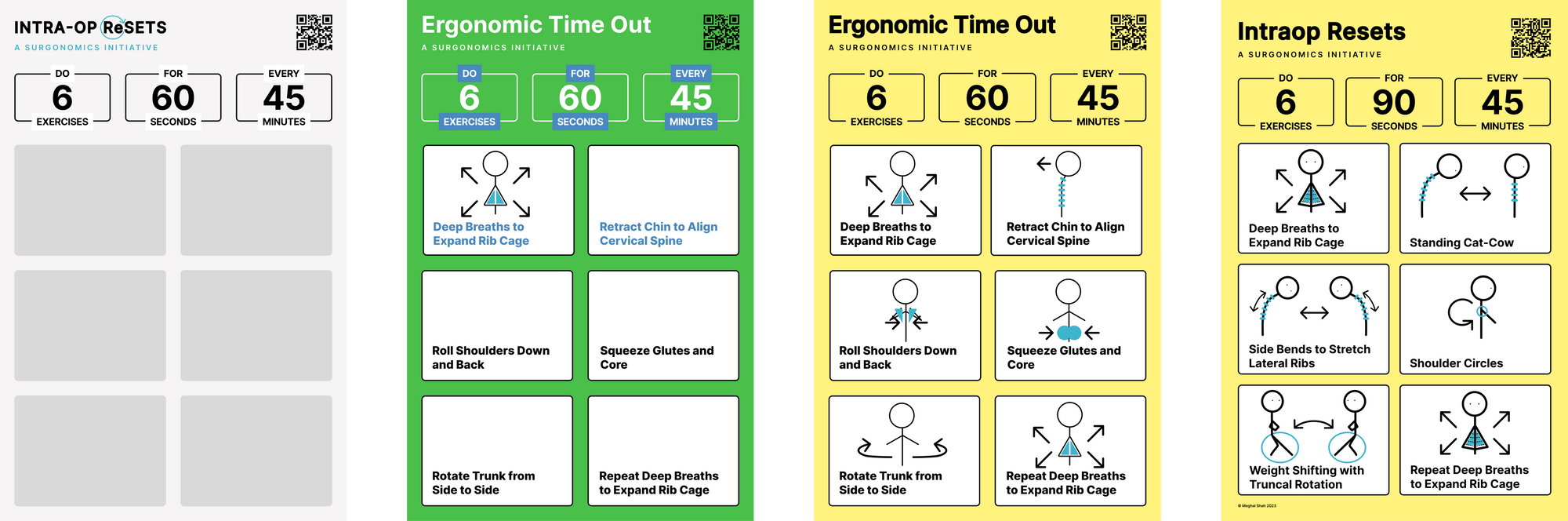

I collaborated with physical therapy faculty at Columbia to curate a set of exercises to counteract the unique stressors of operating that can be completed in under two minutes without breaking scrub. In parallel, we designed a user-friendly poster depicting these exercises with minimalist drawings, a process that was fun and fulfilling, especially when the final design came together beautifully. We went through several iterations of the design, taking into account user feedback (four votes for yellow, two votes for green, preference for stick figures rather than human depictions) and improving on the exercises initially chosen.

The poster serves as a visual cue for microbreaks and is currently hanging in ten of our operating rooms, as well as in all of the operating rooms of a nearby hospital where our residents operate. We hired a freelance graphic designer to make an explanatory video to go hand in hand with the poster. All of these resources are compiled and freely available here.

Emerging from this period of creative productivity felt refreshing - I developed skills (Figma, video editing) and designed resources with cross disciplinary experts.

However, I soon found myself again in my least favorite position - asking surgeons to do something for me. If I were to implement microbreaks in the most effective way, I would be in the ORs, interrupting cases, training surgeons, guiding them through the breaks myself. But just as easily I started the project, I came to a halt. It seemed I had initially underestimated my own social anxiety and fear of being seen as a “disruptor”, or worse, fear of not being taken seriously. How can I possibly walk into an OR and ask the team, who may be focused on the operation, to stop what they are doing and take a “microbreak”?

And so I stalled. I tried to rationalize - culture change is too difficult, behavioral interventions are not effective, there are more important fulfilling things I want to focus on. But if I am being honest, I’m scared of this next step because it forces me out of my comfort zone and forces me to face my social fears head on. In truth, my actual fear is 200 years of surgical culture, and not the people I work with. In fact, the mentors, faculty, and residents around me have been extremely supportive, especially when I’ve doubted myself the most. Perhaps my biggest fears and limitation may also be my opportunity for greatest growth. 1I’ve driven to the edge of the cliff, and the only thing left to do is take a leap of faith.

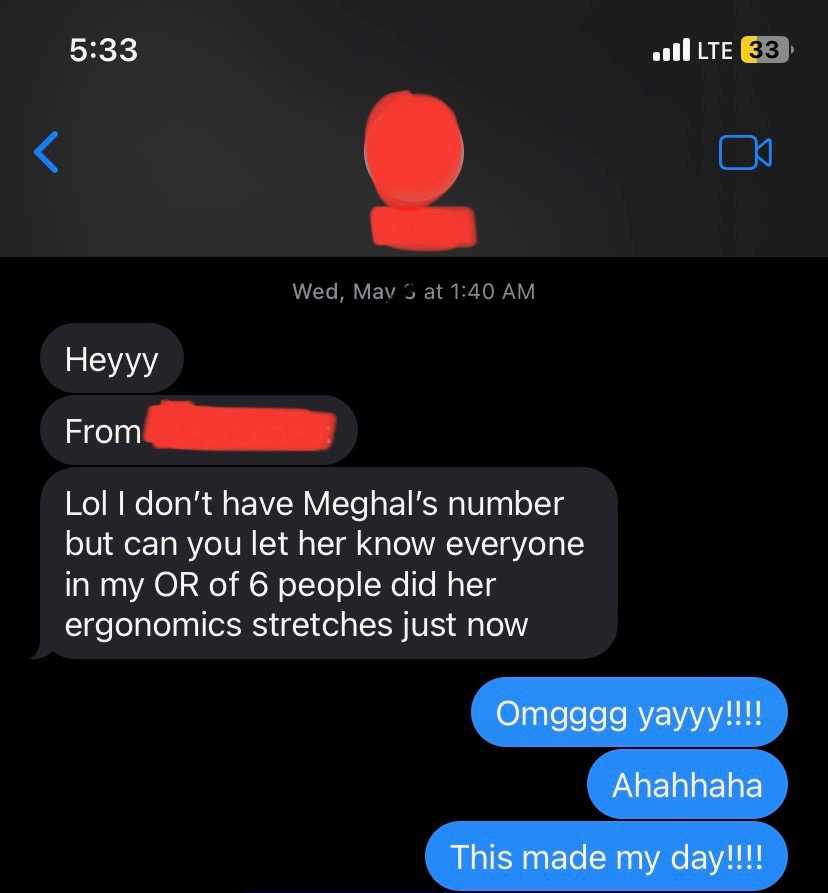

I took that leap of faith and the end result was beautiful. While I was laughed out of only one or two ORs, the overwhelming responses from OR teams were supportive. I found surprising allies in senior attendings including division chiefs, and the perioperative nursing staff even invited me to run a tutorial at their skills day. Over the past few months, countless people have told me their OR did a microbreak, even from departments outside of my own. Text messages like the one here have brought me endless joy and fulfillment. Here is a video of our surgeons leading their teams through microbreaks.

My story highlights a common hurdle that stymies progressive culture change. Often, to create change, we have to ask people in power to change the way they do things. It doesn't even matter if the people in power agree with the change (often they do!) - the nature of this hierarchy makes the task daunting, regardless of the intention or goal. But clearing this hurdle opens the floodgates to culture change. How might we create ways to bother people more effectively? I do not have the full answer but here are a few ideas on how to implement a behavior change intervention such as a microbreak:

Minimally disruptive - If you have the access to the EHR then you can build data collection and educational tools into the existing workflow. If, like me, you do not have this access, then we will be publishing our code to automate text message delivery at preset times. While imperfect, it does automate the creation of a somewhat personal and timely touch to any intervention.

Make things mandatory - As residents, we complete an enormous amount of administrative work, from periodic mandatory trainings on central line safety and human resource slide decks. All of these things contribute to burnout and are undoubtedly disruptive to our schedules, but we get it done because it is mandatory. Perhaps cutting down on these administrative burdens and instead building participation in program improvement efforts into the requirements can be effective and improve wellness.

Reward participation - Reward incentives such as Amazon gift cards or meal vouchers are frequently used to boost participation in surveys. It's only a matter of finding the right incentive for our cohort in that case. In our work, we realized that the most prescient incentive would be to automatically submit cases into the ACGME case log on behalf of residents based on their survey responses. This works even better if there is EHR integration, in which the case data includes the residents who were scrubbed in the case.

Protected time for participation - Many residency programs build protected time into the resident schedules for personal use, administrative tasks, academic work, or any of the above. Similarly building in protected time for quality improvement efforts, exploring human centered design projects, and resident wellness will only serve to cultivate more well rounded, creative, and fulfilled residents.

Finally, sometimes we just have to take the plunge and bother people a little bit. That doesn't mean accosting busy surgeons when things are not going well in a case. But within reason, there is no harm in asking. Some may laugh, some may refuse to participate, some may ignore your presence altogether. But in my experience, most most will be supportive to the extent they are able. And that is how the gears of this slow, painful, and messy process of culture change begin to turn. At the end of the day, I guess disruption does require being a little disruptive.